My favorite new thing is online education. My kids use KhanAcademy at school and at home to supplement their math education. Sal Khan is a particular hero of mine for developing a programming module for the Day of Code. My nine-year-old was coding up simple computer graphics like a pro. There are many, many new online education sites and tools out there but my favorite is Coursera (coursera.org). My husband and I have taken several classes on Coursera since we discovered it early in 2013. He has taken a programming/algorithms class from Princeton as well as some statistics and data analysis classes from Princeton and Johns Hopkins. I’ve taken a course about the ancient Greeks from Wesleyan University, a creative programming course from the University of London, and Archaeology courses from Brown University, Tel Aviv University and the Autonomous University of Barcelona. The last was an Egyptology course in Spanish. The course was very good but my Spanish was only just barely adequate. I did learn some good stuff about Old Kingdom Egypt though, and it prodded me to find a good paella recipe so I’d get the exchange-student-in-Spain feel. My twelve year old son took an internet history and technology course from the University of Michigan and has started a programming course from the University of Toronto.

It feels like we really are living in the future and I love, love, love having new opportunities to learn random things. The classes my family and I have taken have been uniformly excellent. Coursera has a wide array of classes on many different topics. You can use them to learn as much or as little as you want. If you want to just listen to lectures and never take any quizzes or do assignments, you can. Or, you can put in maximum effort and treat it as a serious college course. The due dates and deadlines actually help me to focus and make sure I get the work done. I have been an independent learner for years, but the online course with deadlines gives me a much greater sense of accomplishment. Online discussion forums and peer grading with feedback are a surprisingly effective way to have contact with fellow students. In particular, I enjoy peer grading. When you submit an assignment, five people give scores and feedback. Each person who submits an assignment must also grade five other assignments. It is fascinating to get that kind of diverse response to your own work, and equally fascinating to learn what kinds of things your fellow classmates are working on. The best part is that only the people in the class who were serious enough to do an assignment are part of the grading process. That weeds out anyone who was just lurking around and taking it very casually. The people who are actually submitting and grading assignments are the most engaged students in the class. That means the assignments are almost always well done and the comments you’ll receive on your work are both serious and helpful.

My favorite class so far has been Archaeology’s Dirty Little Secrets developed by Professor Sue Alcock at Brown University. They are offering it again in a couple of weeks. If you have any interest at all in Archaeology or the study of the past, I highly recommend this class. There are outside assignments, but they are not especially difficult and many of them are actually fun.

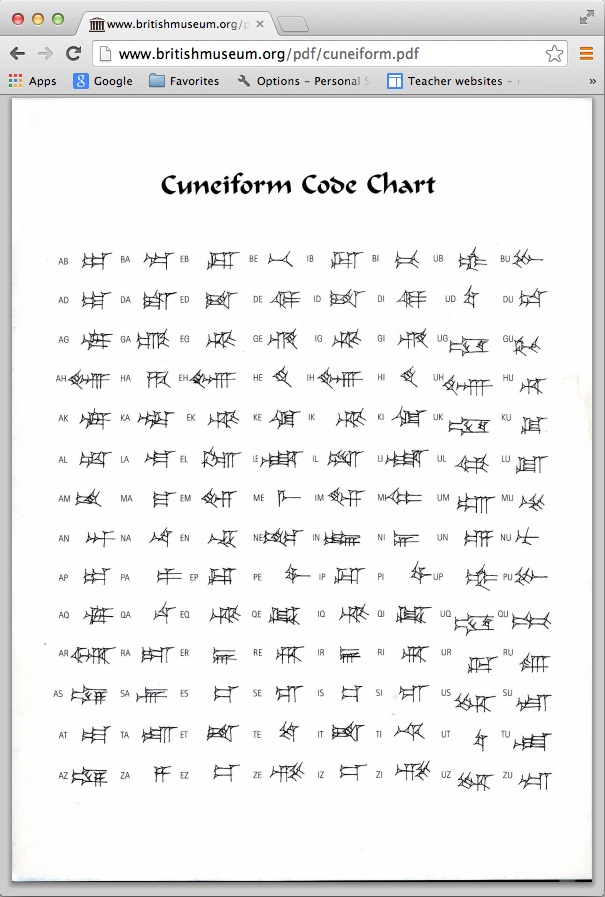

Which brings me to this little project wherein I tried to learn cuneiform writing. You know, the little wedge marks on the clay tablets made three thousand years ago by a room full of Akkadian scribes dedicated to perfecting that one task. Well, I’m an educated sort of person. I spent plenty of years learning to read and write. I even have a couple of foreign languages under my belt. I should be able to do this. The class linked to videos of two grad students giving instruction using chopsticks and Crayola modeling clay. It looked fun. I was on vacation so I wasn’t sure I’d be able to easily come up with the required equipment. But we found a great Chinese restaurant in Champaign, IL (Golden Harbor. Order off the authentic menu. Thank me later.) with just the right kind of disposable chopsticks. I grabbed an extra set. A trip to Target the next day for contact lens solution gave me the excuse to grab some clay. Equipment procured, I worked on my tablet in the car while my husband drove across Illinois and Iowa.

I have a new appreciation for the practice that must have been required to create usable tablets. Sure, you can learn to make wedges pretty quickly. A little practice to get the right pressure and angle of your “stylus” and you’re pretty much there. But take a look at the .pdf file with the Akkadian symbols and you’ll see that there are lots of wedges in some of these symbols, and you have to put them all together correctly in order to make it legible. I messed up several times on the three characters of my first name. I smudged out mistakes and had to re-form the clay enough times that my clay started to dry out. When the clay begins to dry, it takes the impressions differently, which caused me to make more mistakes. An experienced scribe would no doubt know this and adapt his pressure. An inexperienced dolt like myself just makes impressions that can’t be deciphered.

Finally, I started with a new piece of clay and successfully (sort of) made the characters of my first name. I then studied my handiwork and took a look at the characters I’d need for my last name. They looked harder. Rather than add my last name and risk messing up the whole tablet again, I re-read the assignment. It said to write your name. It didn’t mention “full name”. So, there you go. First name was all I could manage in a reasonable amount of time without major errors.

Now, about my name. It’s Michelle, pronounced “Mishel” in Franco-American English, whatever my particular version of the feminized Hebrew for Michael is. So…the cuneiform list I have doesn’t list a symbol for “sh”. Do I use one of the symbols for an “s” syllable, maybe “sa”? My name would then be something like “Mi-sa-el”? That covers the American pronunciation of my name, sort of, but maybe I should go back to the name’s origin and its pronunciation in other languages. Maybe I should use something like a guttural “cha” sound, “Mi-cha-el”. Yes, that might be better. Now, would that be the cuneiform symbol closest to guttural “cha” be “ka” or “ha”? Hmmm… Now I have to confess that I chose the symbol for “ha” over “ka” in large part because “ha” had fewer strokes in it and I felt I’d have greater success making the symbol. Did the ancient scribes ever make this trade-off when writing names or words that weren’t in their own languages? I like to hope they were better at their trade than I am, so they wouldn’t need to stoop so low, but who’s to say…

There you have it. Three characters: Mi, Ha, El to make “Michelle”.

Not particularly good, and much larger in scale than any actual cuneiform tablet I have seen. A real Akkadian scribe could have put a whole peace treaty on a tablet this size (it’s about the size of my palm). Trust me, the Kadesh treaty between Ramesses II and the Hittite King Hattusili III is about the same size as my hunk of clay. I saw it in person in Istanbul and was shocked at how tiny it is. Chalk that up to one more famous thing that’s much smaller in person than it seems to be in the art history books (joining the Mona Lisa, the Phaistos disk, Eiffel Tower, etc.). I have a new appreciation for the scribal skills required to make competent tablets, an even greater appreciation for our good old alphabet, and a little bit of insight into foreign language spelling irregularities in ancient texts.